America is blessed with a wealth of groundwater and surface water that helped create the 20th century America with vast cities, industry and bountiful farmland. That era may be ending. We are using up our groundwater faster than it can be recharged.

The New York Time just published an excellent article: “America Is Draining Its Groundwater Like There’s No Tomorrow.” For the article the Times performed an analysis of over 84,500 of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) groundwater monitoring wells. They found an emerging crisis that threatens American prosperity. The Times analysis found: “Nearly half the sites (groundwater levels) have declined significantly over the past 40 years as more water has been pumped out than nature can replenish.”

The Times looked at the water level in the groundwater wells. This level in a well usually fluctuates naturally during the year. Groundwater levels tend to be highest in the early spring in response to winter snow melt and spring rainfall when the groundwater is recharged. Groundwater levels begin to fall in May and typically continue to decline during summer as plants and trees use the available shallow groundwater to grow and streamflow draws water. Natural groundwater levels usually reach their lowest point in late September or October when fall rains begin to recharge the groundwater again and the leaves fall from the trees reducing their need for water. The seasonality for a long time can disguise a diminishing groundwater supply, but over time the falling level emerges.

Though the New York Times focused on irrigated agriculture, which was the first problem to emerge. Groundwater levels are affected by how many other wells draw from the aquifer, how much groundwater is being used in the surrounding area for agricultural, industrial or commercial use, or how much groundwater is being recharged. Development of an area can impact groundwater recharge. Land use changes that increase impervious cover from roads, pavement and buildings does two things. It reduces the open area for rain and snow to seep into the ground and percolate into the groundwater and the impervious surfaces cause stormwater velocity to increase preventing water from having enough time to percolate into the earth, increasing storm flooding and preventing recharge of groundwater from occurring. Slowly, over time, this can reduce groundwater supply and the water table falls.

Increasing population density increases water use. Significant increases in groundwater use and reduction in aquifer recharge can result in slowly falling water levels that indicate that the water is being used up. Unless there is an earthquake or other geological event groundwater changes are not abrupt and problems with water supply tend to happen very, very slowly as demand increases with construction and industrial use (for data center cooling for example), and recharge is impacted by adding paved roads, driveways, commercial buildings, houses and other impervious surfaces.

|

| from USGS |

|

| from USGS |

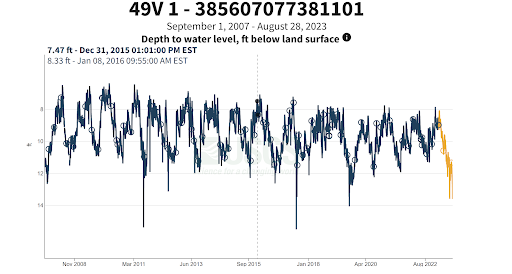

It is clear from the first USGS graph that the groundwater

level in well 49V-1 has falling since

before 2008. The groundwater is being used up. In the second graph you can see

that for decades before that the groundwater level was fairly stable.

Virginia is dependent on groundwater. According to

information from Virginia Tech, the Rural Household Water Quality program and

the National Groundwater Association approximately 30% of Virginians are

entirely dependent on groundwater for their drinking water. In Prince William

County about a fifth of residents get their water directly from groundwater,

but the health of our watersheds and stream flow are dependent on groundwater,

too. While groundwater is ubiquitous in

Virginia it is not unlimited. There are already problems with availability,

quality and sustainability of groundwater in Virginia in places such as

Fauquier County, Loudoun County and the Coastal Plain.

No comments:

Post a Comment